We can learn a lot about ourselves by looking at, and thinking about, perceptual illusions and our biases.

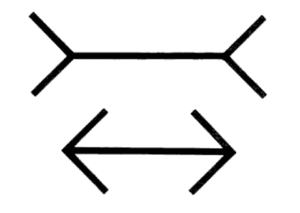

Look at the image above. The classic, Muller-Lyer illusion.

We know that the two lines are the same size. But no matter how much we intuitively “know” this to be true, we see the top line as bigger. We can’t unsee it — even if we try. Why is this?

There’s a difference between your perception of visual reality and concrete visual reality.

That’s a strange concept to consider, so I’ll say it again: What you actually perceive as your visual reality is not what reality is. It’s a combination of visual stimuli and your mind’s “beliefs” and understandings about how the world works, based on patterns it knows. It then tries to create mental shortcuts that help you navigate the world without as much mental effort.

The same thing happens in our cognitive space. There are many mental shortcuts, known as heuristics, that our brains subconsciously create to help us get through the world more easily.

If you haven’t read the work of Daniel Kahneman, you should. His work, summarized in his book Thinking Fast and Slow, will make you think a lot about how you see the world.

Our brains are not the rational, logical machines we once thought they were. We are making irrational decisions all of the time. Based on faulty logic, errors of perception, and emotional influences. They also very much impact how we practice medicine, so it’s important to review a few of them.

Cognitive biases

Anchoring. The tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered up (the “anchor”) when making a decision. In the ER, this occurs when we settle on a diagnosis (flank pain = renal colic) before considering all of the other available evidence.

Availability heuristic. A shortcut we use that relies on easily accessible and recent examples when evaluating a specific topic. For me, if my colleague tells me that yesterday he saw someone with an aortic dissection, I’m more likely to work up the next few patients for dissection than if I haven’t seen a case in over a year. The population risk hasn’t changed. But my interpretation of that risk changes based on my recollection of recent events.

Confirmation bias. We often look for information to confirm things we already believe to be true and often ignore information that dissuades us from that view. If we’ve already anchored on a diagnosis, we have the tendency to look for symptoms to confirm this

and can ignore other subtle pieces of information.

Hedonic adaptation. We return to our baseline level of happiness despite positive or negative life changes.

Of course, our brains take these shortcuts for a reason. If we had to fully process every piece of information we receive, we’d get nothing accomplished.

We’d be walking through the world like a toddler, still working our ways through the challenges of object permanence. Evolutionarily, that’s not an effective way for us to function in the world.

But these mental shortcuts can lead to problems. We often firmly believe something to be true because it’s what we “see” or what we “think.” But we are completely unaware of our blind spots.

Do you have strong beliefs about who you are? What your worth (or worthlessness) is? Thoughts about your current life, where it’s going wrong, and what you need to be happy? That you’d be happier if only “this” and “that” were different. Well, guess what. That’s a cognitive illusion.

We know, from evidence, that our happiness isn’t dependent on external things outside of simple comforts. Yet our minds tell us something different. And because we think it, we firmly believe that we must be true. And much like our other cognitive biases, we make faulty decisions in ways that support these mistaken beliefs. Buying fancy cars, and big houses chasing only what is a temporary happiness. Returning back to our baselines shortly afterward.

Miswanting

In my own life, as a medical student, I figured I’d be happier when I was a resident. I’d be making a salary! And as a resident, I’d be happier when I was staff. I’d be making a bigger salary! But looking back, I was just as content in my medical school days as I am now, perhaps more so. By wishing for things to be different in the future, I was only causing myself to miss out on opportunities to celebrate what’s great about right now. Cognitive bias.

We’re really bad about predicting what our future selves will be like. And we tend to overestimate the effect that events in the future will have on our current happiness. This term has been called “miswanting” by Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert. I also suggest his book, Stumbling on Happiness. Most things simply don’t make us as happy as we think they will. Often they don’t make that much of a difference at all.

The world you perceive and the world you create in your mind isn’t always accurate. Not always. Thoughts are just that. Thoughts. An auditory perception with perhaps a visual and a sensory component. A tingling of a few neurons and the passage of a small electrical current somewhere in your skull. Those thoughts become beliefs when you attach to what you hear and believe it firmly to be true.

Our reality is, in many ways, an illusion of the mind.

You can learn to see through the illusion. It takes time. Practice. Maybe some professional support. But it’s possible to re-examine your life through another lens.

How much of what you believe is objectively true?

How many things in your life that you experience are objectively awesome? Objectively, how great is that sunset? Those flowers? That smile on your lover’s face? The taste of that first sip of coffee in the morning?

Sure, there are things to strive for and goals to attain. But it’s important to realize that you might not be happier when you attain them. In fact, your happiness may not be dependent on the things you achieve. Cognitive bias. Strive for them for achievement’s sake … to push yourself and test your potential. But not to make yourself happier.

Consider this point again. Your mind is constantly telling you that things will be better, and you will be happier at some point later. The cognitive scientists say that that’s just a faulty mental belief pattern.

Who to believe? Look within.

When you do, the things around you and the people in your life become more than enough. The rest is just an illusion.

Navpreet Sahsi is an emergency physician who blogs at Physician, Heal Thyself.

Image credit: Shutterstock.com