The 17th European AIDS Conference (EACS 2019) in Basel, Switzerland, last week, heard about another case of a PrEP user who caught HIV despite being apparently adherent to PrEP.

These cases are likely to keep on happening, Dr Hans Benjamin Hampel of Zürich University Hospital told the conference, and we perhaps need to move beyond trying to establish which – if any – cases of PrEP failure have watertight evidence of 100% adherence. This is so difficult to prove that we may be forever uncertain about how often, if ever, “breakthrough” infections happen when PrEP users take their preventative medication exactly as directed.

“The community would like to believe that this patient was just non-adherent,” Hampel later told aidsmap.com, “because that’s a simple reason for HIV infection.

“But there actually may be multiple factors that influence the efficacy of PrEP, and these may come together to create cases of PrEP failure like this.

“The question is, how should we report them, and how do we want to further investigate them?”

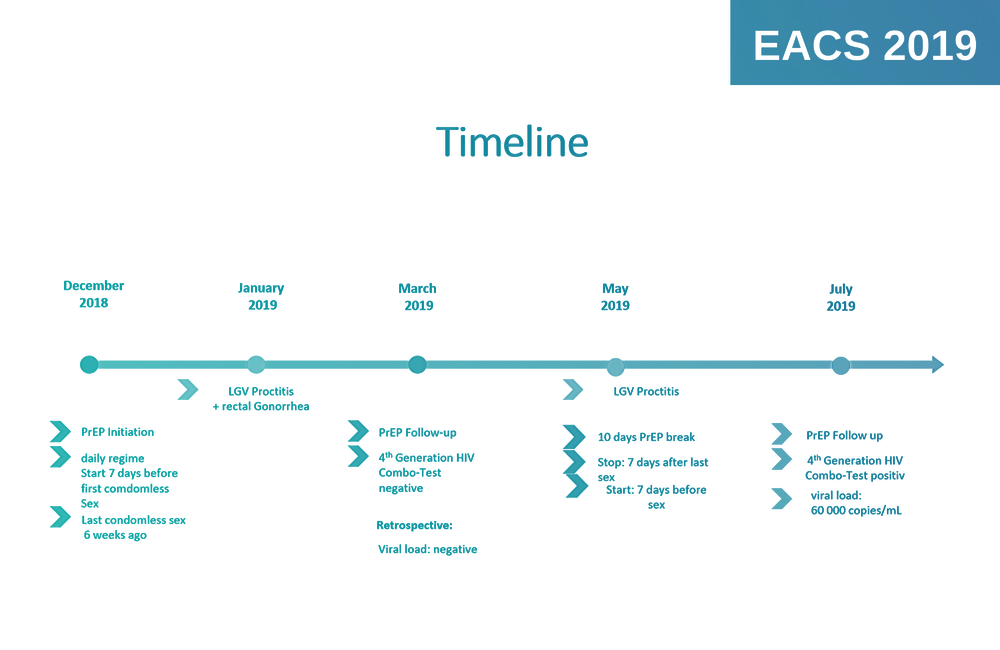

The case concerned a 34-year-old gay man who started daily PrEP in December 2018. He was knowledgeable about PrEP and highly motivated to maintain good adherence. To motivate himself, he kept a PrEP diary throughout his time on it, which is one reason Dr Hampel and colleagues think he might be a genuine breakthrough case despite lacking 100% conclusive evidence of adherence.

“He was also not someone who had the sort of problems that often come with poor adherence, like depression or substance use,” Hampel comments.

He last had condomless sex six weeks before starting PrEP, and started PrEP a week before he first decided to risk condomless sex.

In January 2019 he reported rectal STI symptoms and was diagnosed with lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) and rectal gonorrhoea. Rectal inflammation and LGV have been cited as factors that may have contributed to other cases of PrEP failure, such as the Amsterdam case reported in February 2017.

In March 2019 the present patient had his three-month follow-up visit for PrEP and tested HIV-negative on a fourth-generation HIV test.

In May he was found again to have LGV-related rectal inflammation. It was at this point he decided to take a short ten-day break from PrEP.

“He was travelling with his parents to a very rural area, where there was no chance of sexual contact,” Hampel told aidsmap.com.

“According to his PrEP diary, he stopped PEP seven days after his last condomless sex, and didn’t have sex for seven days after re-starting.”

In July, however, he tested HIV-positive, five weeks after his PrEP break. He had a viral load of 60,000 and his confirmatory Western Blot test showed antibodies to all HIV proteins except the envelope protein gp120.

“To me,” Hampel said, “this is evidence against him acquiring HIV during his PrEP break.

“It would be unusual even in ordinary cases to have such a full near-complete seroconversion within five weeks, and we know PrEP can delay seroconversion. The timing suggests he caught HIV before he took his break.”

“A database of apparent seroconversions on PrEP is planned.”

Resistance and drug level tests also gave suggestive results. His HIV turned out to have the M184I resistance mutation to emtricitabine (FTC), one of the two drugs used in PrEP.

Although this resistance mutation is common and can be transmitted, it does reduce viral fitness and ease of transmission. It has been seen in the majority of cases of apparent PrEP breakthrough where resistance tests have been done. In is more likely to have arisen after infection – from taking PrEP while already infected – than to have been transmitted. Furthermore the more usual mutation is M184V. M184I is most often seen transiently as a “step” towards the other mutation, which also suggests the resistance had happened after transmission.

Secondly, the doctors did a drug level test on the patient the day he was diagnosed. He was found to have unusually low trough levels of tenofovir (the level immediately before the next dose). His levels were in the lowest 10-20% of typical levels. Furthermore his peak levels (the levels just after a dose) were even lower, with tenofovir levels found in the lowest 5% of typical levels, and emtricitabine in the lowest 10%.

“You may ask why we didn’t do a retrospective drug-level test on cellular samples or on hair, as has been done in other studies,” Hampel commented. “The answer is that his PrEP break would have lowered levels anyway, so we can’t use such retrospective tests to measure average adherence.

“The same would apply if he had been someone taking event-driven PrEP on the 2:1:1 regimen.”

In short, this case is perhaps more typical of possible PrEP “breakthrough” cases than ones where it can be shown with 100% certainty that the person concerned was definitely taking PrEP and had adequate drug levels at the time. This, as Hampel comments, will remain very difficult to prove as you have to have a drug-level measurement very close to the time of infection.

It is rather that there were several factors that may have contributed to his PrEP not working:

- He did have a PrEP break five weeks before HIV diagnosis and we can’t rule out that the patient had sex closer to that break than he recalls;

- The LGV inflammation may have increased the likelihood of transmission;

- It’s possible, if not very likely, that he may have caught a virus with a degree of pre-existing resistance to PrEP;

- For some reason (such as efficient kidney excretion) this patient had rather low levels of the PrEP drugs and especially tenofovir in his system. While they should normally have been adequate, they may not have been so if combined with the other two or three factors.

“These cases are likely to keep on happening, and we need to move beyond trying to establish which – if any – cases have watertight evidence of 100% adherence.”

The patient, by the way, is fine. He started antiretroviral therapy on dolutegravir, tenofovir and rilpivirine and had a viral load of only 28 copies/ml three weeks after starting ART. He did, of course, find it difficult to cope with diagnosis in the beginning, having tried so hard to avoid HIV. But he has stabilised and is considering switching to a daily dolutegravir/rilpivirine pill (Juluca).

As Hampel says, in this kind of case we can probably never establish an exact single cause. It is therefore perhaps better to document causes of PrEP failure and build up a database so we can start establishing the more dominant causes, and those less often involved. Such a database of apparent seroconversions on PrEP is planned by the people running the RESPOND cohort, which is the successor to, and an expansion of, HIV cohort studies such as EuroSIDA and INSIGHT.

“Of course, Hampel commented, “We have an insecurity as to whether this really was a breakthrough on full adherence, but at least he documented his intake. That is more than we have for any condom-use study ever done.”