Studies in recent years have shown that cognitive impairment and hearing loss are strongly linked. But for the first time, a new study found that cognition may be impacted even when hearing loss is slight.

be taken as seriously as hearing loss in

children, Golub said.

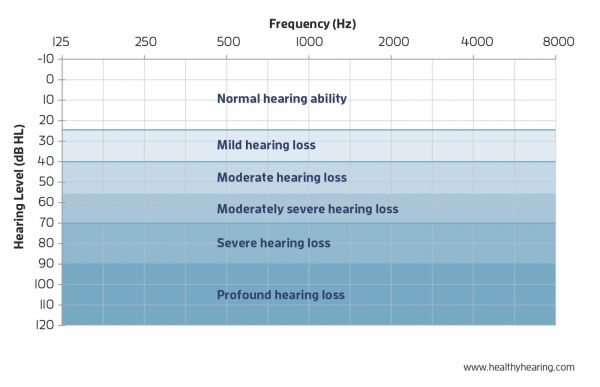

Typically, adults who can’t hear sounds quieter than about 25 decibels (dB) are considered to have hearing loss. The new study indicates that the 25 dB threshold may be too arbitrary, and that “sub-clinical” hearing loss needs to be taken more seriously, said Dr. Justin S. Golub, MD, lead researcher and a physician with the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University. For reference, 25 dB is about the sound level of soft whispering.

‘Good but not perfect hearing’

The cross-sectional study looked at two sets of data, encompassing nearly 6,500 people who had an average age of 59. Study participants underwent hearing tests, and took several cognition tests. Researchers found measurable and “clinically significant” declines in cognition in people with slight hearing loss—people who struggle to hear sounds quieter than about 15-20 dB. This is a level of hearing loss that wouldn’t normally trigger a more formal hearing evaluation.

“The surprising thing about this study is that the relationship (between hearing loss and cognitive decline) began even in people who had ‘good but not perfect’ hearing,” Golub said in a podcast with the Journal JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. “This is among the first evidence that this association may begin earlier than previously thought.”

‘Age-related hearing loss really is a problem’

Once thought of as a relatively harmless consequence of getting older, age-related hearing loss—known medically as presbycusis—is now linked to several health conditions, including cognitive decline, depression and an increased risk of falls.

“In the past decade, there’s been more and more evidence that age-related hearing loss really is a problem,” Golub said. “If you think about it, it makes sense: If you can’t hear, you might not be as aware of your environment and you may be more prone to slipping and falling. And if you can’t communicate with your loved ones…you’re more likely to be depressed.”

Researchers have been assuming the relationship between hearing loss and cognitive decline is “dose-dependent,” Golub said, meaning that the more hearing loss you have, the more likely you are to have cognitive decline.

“It’s been assumed that this relationship exists when people have hearing loss,” Golub said. “But the 25 dB threshold is really kind of arbitrary. No one has looked at the effects earlier, below that.” (The threshold for children is 15 dB, for example.)

Hearing tests may not be sensitive enough

This is still an area of emerging research, though—scientists do not know if cognitive decline is a result of hearing loss, or if cognitive decline simply occurs around the same time as hearing loss sets in.

“There are some theories,” Golub said, “that link worse hearing with worse cognition. People who have hearing loss have to spend more mental energy decoding words. And they have less mental energy to make memories.”

In an editorial accompanying the study, several audiologists cautioned that more research is needed. In studies like these, it can be hard to control for factors that may influence the results, such as socioeconomic status, said the authors, who were all affiliated with the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health at Johns Hopkins University.

“Before any formalized conclusions regarding this association can be drawn, more work is needed on how hearing that is classically defined as normal is associated with cognitive performance,” the editorial said.

When speech in noise is a struggle

That said, if the findings can be replicated, it may argue that the 25 dB cutoff for adult hearing loss needs to be rethought—as well as traditional hearing tests, the editorial authors said.

For example, standard hearing tests commonly include sitting in a quiet booth and listening to a series of “pure” tones at different pitches. Greater emphasis may need to be placed instead on tests that measure “speech in noise,” which require more cognitive abilities than the pure-tone test.

“The use of pure-tone average may be an inappropriate way to define hearing in the association between hearing and cognition,” the authors said.

Hearing aids are low-risk intervention

The study noted that only about 3% of adults who have mild hearing loss wear hearing aids, even while evidence is essentially piling up that it is not a benign condition.

“Treating hearing loss is very low risk and the potential benefit is high,” Golub pointed out. “We very much encourage children with mild hearing loss to get hearing aids. Why this discrepancy? If it’s good for our kids, why isn’t it good for adults? We really need to think about hearing loss as a bigger problem with adults that we need to treat earlier.”