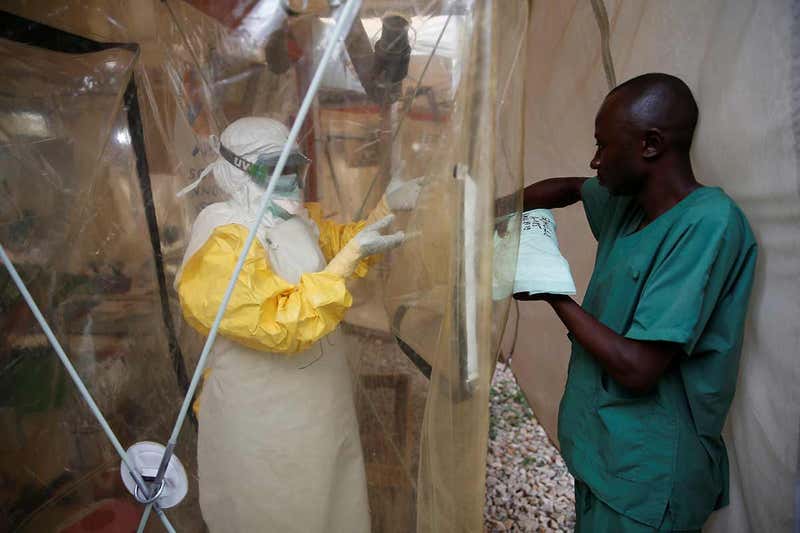

REUTERS/Baz Ratner

At least half of all Ebola outbreaks may have gone unrecognised, and more surveillance is needed to identify them early, before they get out of control. Those are the conclusions of a new analysis involving data from the largest Ebola outbreak in history.

Ebola is a horrifying disease. While it starts with similar symptoms to the flu – fever and chills, muscle pain and headache – it often ends in internal and external bleeding, and death.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is in the grips of an outbreak that has infected about 2000 people and caused 1400 deaths since beginning in August last year. Now authorities have confirmed that it has spread to Uganda, following the death of a 5-year-old boy and his grandmother.

Advertisement

This makes the outbreak the second largest in history, behind the epidemic in West Africa that killed more than 11,000 people between 2013 and 2016.

However, such outbreaks are relatively unlikely, because it is far from inevitable that Ebola will spread between many people if it “spills over” into the human population from bats or other animals. As such, Emma Glennon at the University of Cambridge and her colleagues suspect that more often than not, when Ebola enters the human population it will die out before it grows into a medical emergency on the scale of the current epidemic.

To test their idea, Glennon and her colleagues used computer modelling informed by three separate data sets related to the West Africa epidemic: one on all reported exposures in the outbreak, another with information on cases in a single district of Sierra Leone and a third with data on chains of transmission from early cases in Conakry, capital city of Guinea.

After taking into account the factors that determine the likelihood of the virus passing from person to person, they estimated that more than half of spillover events go undetected, implying well over 100 cases of Ebola have never been picked up by medical monitoring. One of their models suggested that the undetected spillover figure might be as high as 83 per cent.

Infected bats

These spillover events might occur when someone eats an infected bat, enabling the virus to spread to humans. But in most cases, these outbreaks won’t reach more than five people before dying out, the authors say.

Single cases are likely to be the most common outbreak size, but only two countries have reported these so far, they say. According to the team’s modelling, the chances of a single infection being reported is less than 10 per cent.

“Early detection of outbreaks is critical to timely response, but estimating detection rates is difficult because unreported spillover events and outbreaks do not generate data,” the authors write.

Ian Mackay at the University of Queensland in Australia says identifying outbreaks early when only a few people have been infected is vital, because it avoids a difficult and expensive situation of catch-up after dozens have been infected.

He says the study also sheds light on curious trends that virologists have noticed in the decades since Ebola was discovered.

“We have seen studies come out over the years from the 1980s onward showing indications that some people have antibodies [to the virus], but we haven’t seen that to be a part of ongoing outbreaks,” says Mackay.

That could possibly be explained by an infection with a similar virus, or people not remembering if they were part of an outbreak, he says.

“But if we’re seeing half or even up to 80 per cent are missed, that might contribute to these strange antibody results.”

Journal reference: PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases , DOI: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007428

More on these topics: